The Peukert Effect

Present in all batteries. Worst in lead acid

Motivation

If you're designing an EV (Electric Vehicle), choosing an EV to buy, or

just driving an EV, it is worth your while, in big dollars and cents, to

understand the Peukert Effect.

The following description requires high school math to work through

but just paying attention to the conclusions can have big payoffs.

References are listed at the end of this page.

Basics

The "amp-hour" (AH) rating of your EV's battery pack is one of the principle

determiners of EV range.

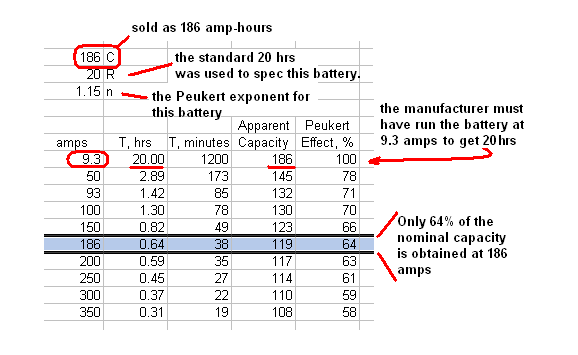

The manufacturer's amp-hour rating for a battery might read "186 AH",

suggesting that you can draw 1 amp for 186 hours, 46.5 amps for 4 hours, or

186 amps for 1 hour. For a common lead acid battery, the reality for the

highest current example is that you'll only get the 186 amps for roughly 38

minutes, 64% of the hour you expected. The battery seems to hold 119 amp-hours,

not 186 (see the blue line below).

If you draw half the current of the above example, 93 amps, you might expect it

to run for twice the time, 76 minutes. But the battery will

deliver for 85 minutes, 2.23 times the 186 amp time. The apparent capacity also

goes up 2.23/2, to 132 amp-hours. Note the downward trend in the Apparent

Capacity: as the current draw (EV speed) increases, the capacity (range)

decreases. You can drive farther if you keep the current (speed) low

.

These kind of results should serve as a warning that something

non-intuitive is happening here. And, if you should get comfortable that

your EV regularly travels X miles at 45mph then, another day you drive the

same route at 60 mph, you can be surprised that batteries are exhausted

before you reach your destination. While walking the rest of the way, you

can ponder Peukert's Equation.

Peukert's Equation

The table above comes indirectly from the Peukert equation below. His

original equation, shown in the Wiki article, been slightly rearranged to

improve readability and to use the slightly different symbology given in

the Smartgauge articles (see References). 'Cp' is Capacity as Peukert

measured it but, throughout this note, 'C' (not 'Cp') will be represent

the capacity of the battery. 'C' will be the capacity stated in the modern

way, measured over a period of 'R' hours (usually 20).

The exponent is all-important. If it were 1.0, there would be no Peukert

Effect to discuss; a 186 AH battery would deliver 186 AH at all currents.

The closer the exponent is to 1.0, the more perfect the battery.

For deep cycle lead acid batteries, the exponent 'n' is 'typically around 1.1'

and, as the batteries are used, that number eventually creeps up to 1.3 or so.

A review of

The Battery Table

, however, shows that real world batteries have exponents ranging well beyond

1.3 !

All types of batteries, even Lithium Ion (Li), have the Peukert Effect to some

degree. For efficient batteries, like Li, their exponents are just nearer to

1.0 than lead acid. Compare the exponents for Li vs LA (again in the same

battery table referenced above).

Smartgauge corrections, explanations

The original Peukert equation has been reverently carried along for over a

hundred years but few have really challenged it. More than one text on

EVs advised just treating the Peukert effect as a constant 57%, independent of

current, exponent, or anything else. Fortunately, Smartgauge noticed the

traditional equation didn't work with present day conventions and they published

the adjustments. For years, articles had been publishing the unusable form of

the equation - and nobody noticed.

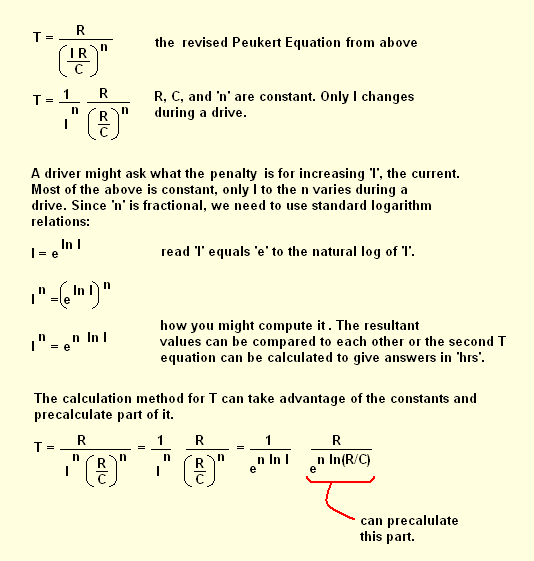

The key to their adjustment is to add a value, 'R', in the following

to represent the number of hours used to quote the amp-hour rating ('C')

for a battery. The following starts with the Smartgauge 'adjustment' and

just shuffles it a bit for readability.

Calculating with Peukert's Equation

With the SmartGauge corrections in place, it's time to figure out what

the range penalty is when the current is increased.

The note about 'pre-calculating' above has to do with applications

which will convert a number of current measurements into Peukert

values. The 'pre-calculate' term, containing only unvarying quantities,

can be calculated before the current measuring begins.

The spreadsheet equivalent is shown in

excel equations.

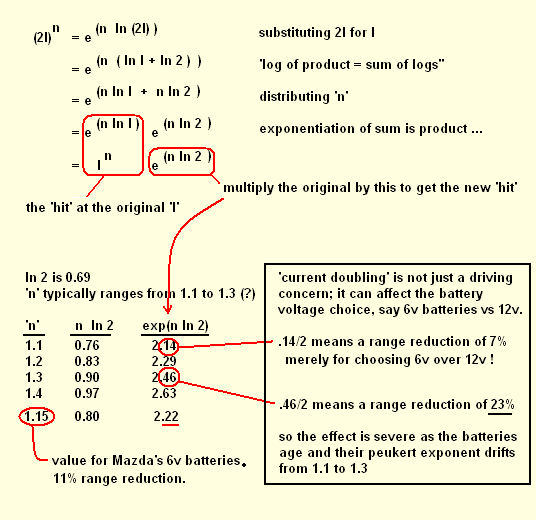

Range effects of doubling the current

This section tests the Peukert Equation with a conceptually simple

scenario, that of doubling the current. This doubling could be the

result of accelerating more aggressively or going faster. Another

interesting instance arises way back in the EV design stages when the

battery pack is designed. In principle, a pack built of 12 volt

batteries will have twice the voltage and half the amp-hours of a

similar pack built of 6 volt batteries (the next section addresses

the realities of this assumption).

The following algebraically modifies the Peukert Equation to compare

2x current with the original current. Whereever 'I', the amperage,

appeared in the earlier equation, we'll just substitute '2I' and see

what the effects are.

Choosing batteries, the reality show

While the logic of the last section is certainly sound, there are at

least two 'real world' problems to address. The minor one is that

the logic above posited that you were faced with 2 battery choices,

probably of the same weight and thus, theoretically, the same

total energy. One battery produced that energy with, say, 12 volts

and 100 AH while the competitor produced it with 6 volts and 200 AH.

It isn't so easy to see this 2x business while looking through a

table of real batteries. And, more importantly and much more subtle

is the range of peukert exponents. What if a 6 volt battery has a

much better peukert exponent than a considered 12 volt?

The tougher problem, at least for the average car conversion

enthusiast, is that the pack voltage is limited to 120 or 144 for

the less expensive, "brushed" motors. So the typical

"series wound" motor is going to impose a low voltage

limit which negates any options for considering high voltage, low

amperage configurations. So early in the design of the car or

its conversion, a PM (Permanent Magnet) DC motor or an "AC

Induction" has to be selected to avoid the range penalties

calculated in the last section.

The simultaneous consideration of so many important factors (pack

voltage, motor choices, car weight etc) led me to write a computer

model to assist making such choices; it is principally focused on

the "battery issue". A great calculator (and one I don't

have to support) can be found at

EV Convert. A

sample session, with choices pertinent to my EV is shown in

this link.

Peukert's effect on driving style

In principle it should be obvious that keeping the currents low is very

desireable in an EV, especially when the Peukert exponent is large, because

of battery type or age. But, there was another surprise lurking in this study.

A check of Peukert values over a range of typical currents for my pickup

truck showed that all "reasonable speeds" had Peukert effects

in the 66% to 71% range. The currents were already too large to enjoy small

Peukert effects in the 90% range. Being on the flatter part of the curve,

a 125 amp draw (plus or minus) wasn't, in the Peukert sense, going to

make much of a difference. The range effects of the higher current draw were

really due to the weight and poor aerodynamics of the truck.

The total effect on driving style can be simply summarized:

- try to keep the current low when accelerating away from a stop sign

or stop light. This means 'accelerate slowly', assuming conditions allow.

- avoid stop signs. You're guaranteed to have to stop and replace the

energy of previous motion. Even if you make some of the lights on an

alternate route, you're ahead. A government study claims that 6% of American

transportation energy goes into heating the brakes.

- try to find a time on the freeway that gives a continuous (not stop-and-go)

flow at an efficient speed.

- avoid hills whenever possible. The higher current to climb the hill is

never offset by the free ride down the hill.

Referenced articles, spreadsheets

- ev.c computer model for choosing batteries and

other EV attributes. (web page is still a work in progress).

- Wiki article on

Peukert's Law. Terse.

- Smartgauge articles. A

great explanation of the math.

- A copy of a very thorough study of

EV-compatible batteries, by Chris Jones, EAA, Santa Rosa.

- A modest listing of EV batteries, The Battery Table.

- The author's simple excel spreadsheet.

- How to input excel equations.

- Brant's book on EV conversion.

file: REDSTICK/car/peukertEffect.html

![]()

![]()